So normally, I’m an outside-in writer. I’m obsessive about film and TV structure, and I’ve taught it at USC, the Sundance labs, and all over the world. This is me teaching TV writing in Saudi Arabia with the US State Department’s Middle East Media Initiative in 2019 —

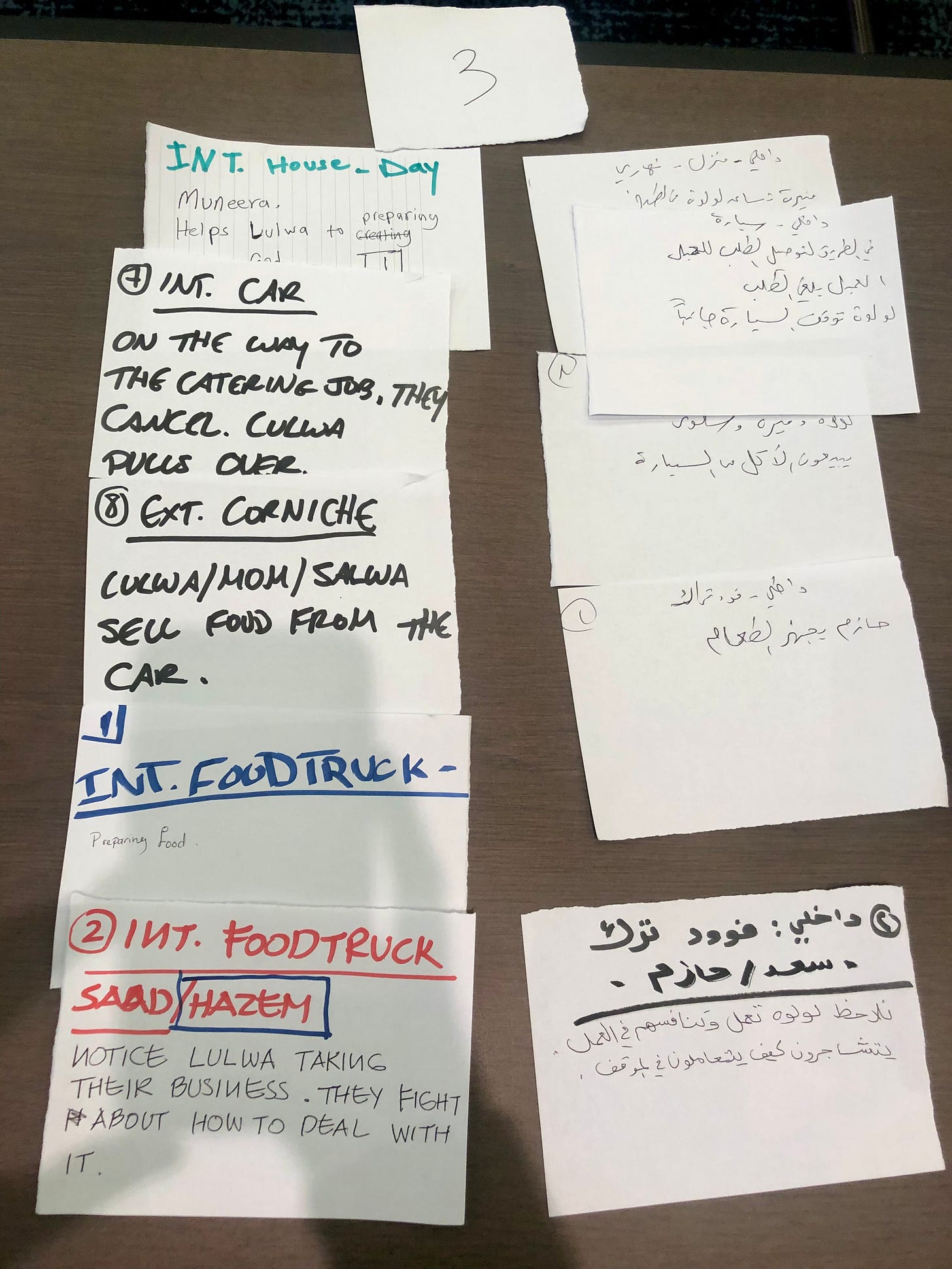

And this is what cards look like in Arabic (which I think is so cool) —

I love outside-in writing. I build a strong foundation, then a scaffold, before I construct the actual building. I’ve seen writers get lost in scripts without strong structure, and that slows the process down. When you’re making content for streamers and networks, agility and speed are key. If you want to see how I do structure, here is a link to my Sundance Masterclass on writing. It’s $30 and it all goes to the amazing Sundance organization.

But even before we started writing CALIFORNIA SCENARIO, (←-psst, click here to help us), I had been wondering what it would feel like to try writing a script the way I write freestyle prose and poetry. (My first poetry will be published HERE later this year!). On a walk, my close friend Kathy leaned in when I expressed that urge. “Then, why don’t you?” She asked. I thought about what the queasy feeling in my stomach meant, and realized, “I’m scared.” She loved that. “OF what?”

“What if I get lost and I never come out?”

Which brings me back to the end of my previous post.

and I had just been granted the extremely rare opportunity to shoot in Noguchi’s Costa Mesa installation, California Scenario. We also knew we could afford… nothing else. No other locations. None. Which left us with two places on planet Earth where we knew we could shoot for free: our homes.In lieu of structure, I was gifted those parameters. Four days at California Scenario, two days at my house, two days at his house. We might be able to shoot about 10 pages a day if James could plan it meticulously, which meant a total of 80 pages. And we knew the subject matter was influenced by our cultural backgrounds, how that affected our present-day lives, and what it’s like to navigate divorce and single parenting. I decided not to think about the structure. Just about the characters, and what the visceral core was to each scene. I tried to get closer and closer to that.

I showed James the pages. He clicked into the material, quickly understanding what this process would look like. And soon, he began to write, too. I’d pass off scenes. He’d write his own and pass them to me. Often, other than discussing a direction like, “we need a scene where the mother and the daughter try to connect, but something stops them,” we had no idea what the other would write.

And in those raw pages, I discovered some of the most painful emotional truths of my career. And some of the most tender, hopeful moments I’ve ever written. Some scenes didn’t work. Or they went on too long. I put them in a box for another day. Maybe another project. But each draft of each scene brought me closer to shining a light on some darkness I’d been afraid to face for a long time.

And what I had feared — that I would get lost — fell away. Instead, from the inside-out, we built what a friend reflected back to us is “a middle-aged coming-of-age story.”

I don’t want to write all my scripts this way. But I learned so much from the process. The problem with doing this writing thing for such a long time is that you accumulate a bag of tricks to some extent. Writing for a paycheck often means solving others’ problems with a story. And when you need to fix something, you use a trusty tool. But throwing my toolbox into the river and then jumping into the rapids to swim freestyle? There was so much discovery. I am more terrified of anyone seeing this movie than I have been of anything else I’ve ever done. It’s the definition of thrilling. And I can’t wait to carry that into my next writers’ room.

NEXT TIME: Wow. We have a script. Now what?